Sevve Stember is a 6th grade science teacher and soon-to-be Director of Curriculum and Instruction. He is an all-around outdoor athlete who has previously written for the American Alpine Journal. You can find him on Instagram at sevve.elliot. This is his first piece for Thundercling.

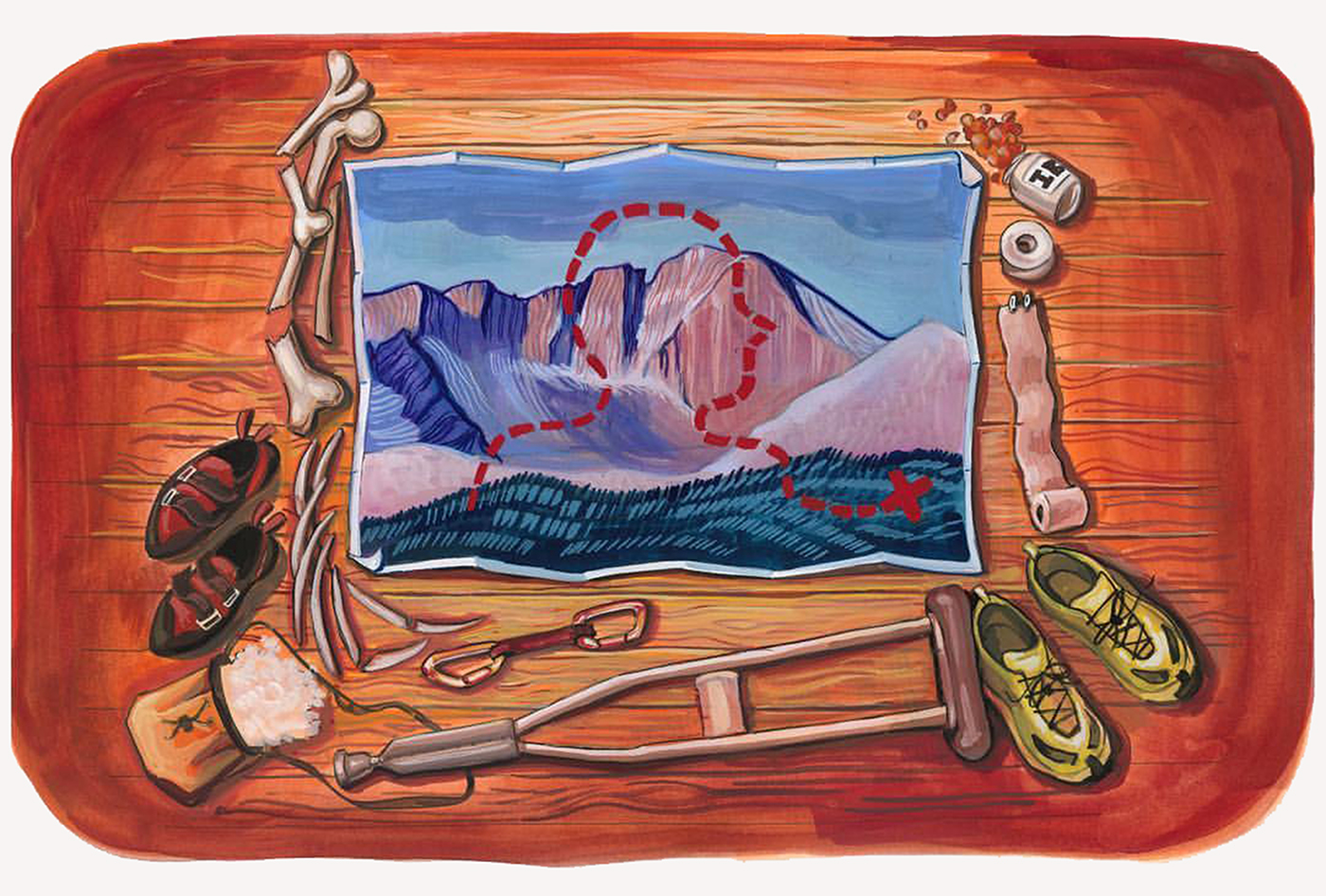

Original artwork by Lynn Suyeko Mandziuk.

Breathing hard, I was running through wind and rattlesnake country. Wide open prairies rolled up and down as far as I could see. Like a mirage, I saw a beat-up truck parked with a man in a sombrero and tattered poncho. This was the halfway feed station of the Dolomite Dash, a half marathon that was part of the Lander International Climbers Festival. “Tequila?” he asked, hands on his hips, as if this was a perfectly normal question. I opted for chips and salsa, which I apparently can’t refuse, even while racing. An hour later, I crossed the finish line, limping. Should’ve had the tequila, I thought.

My crew had gathered to share stories about the race, stretching and unwinding. Propping my leg against a fence post, I stretched my calf. It’s going to hurt either way, I thought. Feeling calorie deficient, I devoured as many eggs, pancakes, and slabs of bacon as I could get in two passes through the breakfast line. Physically wrecked, with bellies dangerously stuffed, we traded our running gear for quickdraws and started the approach to pull on some limestone pockets.

During the race, I had conceived a mini-challenge for myself – run a half marathon and climb 5.12 in the same day, something I hadn’t done before. We warmed up and headed straight to Rising from the Plains, a 12b that had been recommended years ago. Andy hung draws, I flashed it. We’ve all felt it, those fleeting moments of infallible confidence on route, in a relationship, at work. Despite a mediocre race, I was back to feeling psyched. Although my legs were a little rubbery, each micro edge that I placed my foot on may as well have been a jug.

Why not another? I asked myself. We opted for Chorro, an aesthetic 12b that climbed a fiercely pocketed steep belly at the bottom, only to yield slightly into a sneaky steep and clean face interrupted by the occasional crimp or two-finger pocket. Technical and cranky. Things were going well on my fourth try. I made it through the crux and set up for a stabby move that I’d previously stuck. As I arrived at the correct height for the dead-point, my body finally gave up the ghost. My middle finger stubbornly lodged itself in a tiny mono as the rest of my body lurched upwards, putting a fierce side-ways torque on my middle finger. I fell.

Waking up, I didn’t want to look at my finger. I could feel how swollen it was. I unzipped my sleeping bag, sat up, and begrudgingly peered at a finger that did not resemble my own. It looked like a fat sausage link. Taking my first step out of my tent resulted in falling over. My left foot shot pain up my entire leg. I could barely walk. My standard “bigger is better” approach had run its course, as it had many times before, leaving me wrecked. Bigger isn’t always better and my drive to push myself occasionally results in a train wreck, leaving me to pick up the pieces of my life, which never quite fit back together the way I’d hope for.

I had been in Lander for four days hoping things would improve; maybe my broken body would pull off a miracle. It didn’t. With great hesitation and a crushed spirit, I pointed my wagon south back to Denver. Ten Sleep Canyon was where I had originally planned on going, but my finger would be out of commission for months to come. Even if I could climb, my foot was an excruciating menace. I had to call it.

One of the things I love most about the climbing community is how impassioned, committed, and psyched it is. The only problem is, what happens when you lose the one thing that you pour your heart and soul into? Who are you? What’s your identity? Who are your friends? Where do you travel? What do you do with your time? These are all questions I pondered as I drove into the setting sun. One conclusion I came to over and over again was that things would look different for me in the coming months.

*

“Look at our lives!” I roared to three women, headed the opposite direction around the 17 mile loop Charlie and I were running that day. They responded with some yips, hoots, and hollers.The five of us were perched on the Continental Divide at around 11,500 feet a stunning ridge; grassy tundra, sweeping expanses to the east and west, a single track trail weaving its way through an unforgiving landscape. Nothing but rock, mountain, and sky. Completing the High Lonesome Loop would solidify, likely for the rest of my life, a love I was steadily gaining for big trail running days in the alpine wilderness.

That night, gathering every map I own of Colorado, I feverishly hunted for more alpine loops, a familiar craving surging somewhere between the heart and the gut. This is the addicting part of climbing. It’s not actually climbing, it’s the feelings we associate with it, like psych and self-discovery and human connection. Though unable to climb, I re-connected with why I started climbing in the first place. Climbing presents an opportunity to be outside in an engaging and challenging way. It didn’t matter that I wasn’t pulling hard moves. What mattered was that I found myself in an inspiring setting, pushing myself, doing something I love, with people I care for. Sure, the physical act of making gymnastic climbing moves, at the outer limits of my physical ability, had momentarily disappeared. Oddly, the psychological payoff remained. Each weekend I set my mind to an objective that deeply motivated me. The planning, logistics, attention to dietary needs, and a bundle of other OCD climberly fixations all transferred to a new adventure sport.

*

My alarm screamed at me. I hadn’t gotten more than three hours of sleep. Mark and I were planning to meet at the Wild Basin Trailhead in Rocky Mountain National Park at 6:30 AM. Driving through Nederland, CO, my phone beeped. “Dude, not going to make it. Sick. Sorry.” Mark had bailed. When I arrived at the trailhead, I was totally unable to keep my eyes open. I slid into sleep, shivering in my front seat.

Later that morning, huddled behind a granite boulder atop the Boulder-Grand Pass, I made predictions at the wind speeds. 40MPH? 50MPH? The first nine miles flew by. Despite a slowly dwindling drowsiness, my fitness had never felt better. The weather flirted with developing into a full-fledged storm, but I knew better than to be fear-mongered by a gaggle of dark clouds. The summit of Mount Alice still loomed somewhere above me, hidden in the clouds. An even greater unknown was the descent down the Hourglass Ridge. Would I see snow, ice, naked exposure, maybe all three on the other side? I guess that’s the compelling part of adventure. We just don’t know what the hell we’re going to find and how we’ll handle it. These thoughts, coupled with the raging wind, had me puzzled as to the best course of action. Tuck tail down the pass or head towards the summit into the unknown?

Squinting into the gusts I saw a fellow making his way down the summit of Mt. Alice. We discussed conditions and they were good enough to tip the scales in the direction of continued ascent. I paused briefly on the summit and stared down the aggressively steep Hourglass Ridge. My line of sight abruptly ended after 100 feet of snow and rock; beyond that the world was devoured by a swirling, impenetrable fog. “Fuck it. I’m in,” I whispered to no one in particular, slowly descending into the abyss.

Every 100 feet, I’d pause briefly to reassess my decision making, every cautious step a reminder of my solitude. I expected to reach a point where I cliffed out, the snow and ice growing too treacherous to continue. After 30 minutes of tedious down climbing, the fog began to clear and I reached a point where I could see beyond my Class 3 ridge to the less exposed glacial moraine beyond. Adrenaline surging, I scanned the horizon from Chiefs Head Peak to Pagoda Mountain to Longs Peak. I was utterly alone. There was nowhere I needed to be and no place I’d have rather been. Everything, if only for a fleeting moment, was just as it should be.

We are all alone, regardless of whether or not we realize that. Sure, there’s technology to distract us and people near us at almost every moment of everyday but when you strip away the curtain, it’s really just you. Maybe you’ve done a good job of crafting an identity as a lawyer, strong boulderer, musician, etc. etc. Yet, that’s not all you are. There’s more to each of us. I had poured a lot of myself into a couple cups, which I thought would always be me. As I navigated the twists and turns and dead ends, I came to understand how reduced this point of view really is. Because I, for that period of time anyway, was not a “climber.” And if I wouldn’t always be those couple of facades, then a really honest conversation with myself about what actually matters had to come next.

*

The trailhead was closed. A 26 miles day morphed into a 32 mile day in a few seconds. Brandon, always down for an adventure, parked the car and started stuffing calories into his running vest. The rain began before we even reached the trail. Still, Brandon and I feel into the groove as the trail sped past us. That familiar lonely magic descended on us through the swirling sleet and fog. I would have bet there wasn’t another soul in the Indian Peaks Wilderness that morning; just us, alone, a metronome of rubber meeting rock our only companion.

At mile 18 we stopped for calories. My core temperature immediately plummeted. We still had 14 miles to go. Concerned and shivering, I told Brandon I needed to get moving to warm up. We had both hit a mental low point and were struggling. Nothing to do but keep moving. We summited Buchanan Pass just as the snow was picking up. Staring down into a foggy abyss, we dumfounded. What planet were we on? Our eyes never locked, no words were spoken, and yet, we both knew we had done it. Thousands of footfalls stretched before us, but the remainder of the run would pale in comparison to what we had already done. The next four miles would fly by as we entered into the flow – our feet reacting perfectly to each unique undulation of the trail.

Through the many shitty and heart-wrenching moments that clutter our minds there are also those simple moments during which we accomplish some sort of personal benchmark. These crystalize in our memories for years to come, like a small present to unwrap when we need it most. That’s one of the things that keeps me coming back for more as a rock climber or adventurer – we are able to transcend personal limitations through our individual thirst for more and collective energy as humans. That day on Buchanan Pass marked my first ultramarathon distance run.

*

Mile 21 of the Moab Trail Marathon had not gone swimmingly. I’d almost unraveled getting through a heinously sustained two mile climb up to the final feed station. I hydrated, ate pretzels, chased them with a Gu, enough to re-energize me after almost coming unglued. Some people believe in crystals and chakras; I believe in sugar. An impending bonk was mitigated by the Glucose Gods and I paid them tribute by pressing on, my pace quickened and focus sharpened. I spent the next two miles uncoiling a sinuous descent through a geological looking glass, the sedimentary layers running from beige to deep rust. The Colorado River cleaved the landscape, the cliffs reflecting off the slowly flowing water, the whole scene stoic and uncaring. I have my unresolved struggles and missed opportunities and botched relationships. None of that mattered. At some later point, all that would come back into focus, but not now. For the time, it was just motion, breath, and a naked landscape in front of me.

There is a deep satisfaction in breaking the tape at the end of one’s first marathon, but this race signified more than one of life’s “firsts.” It represented a paradigm shift towards being able to deal with the inevitable adversity of life. I’d unwittingly constructed a new version of myself by preparing and training and running the race itself.

In prior years, losing my ability to climb would’ve broken my spirit. In many ways, that year of injury and angst and subsequent discovery had stripped away layer upon layer of who I thought I was. When I found myself at a crossroad, not knowing what to do, I tapped back into what had originally galvanized me to the climbing community. I reckon a bum wheel and trick finger allowed me passage back to my roots with a new appreciation for self-discovery in the outdoors, the opportunity to spend time with people I care for deeply, and adventure. That hesitant transition into trail running allowed me access to those characteristics which inform the best parts of myself.

Ego and stout grades were not the original reasons I dedicated myself to rock climbing. Somewhere along the way, I had lost sight of why I climb. Confoundingly, I could only regain the perspective of why I climb by not climbing at all. All of those confusing and infuriating setbacks had offered me an opportunity to discover more about myself, simply because I let them in. From a place of brokenness I was given a path to a truer meaning of my adventurer’s heart.

Nice work.