Original artwork by Lynn Suyeko Mandziuk.

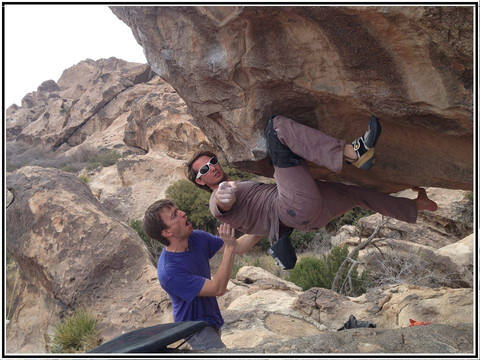

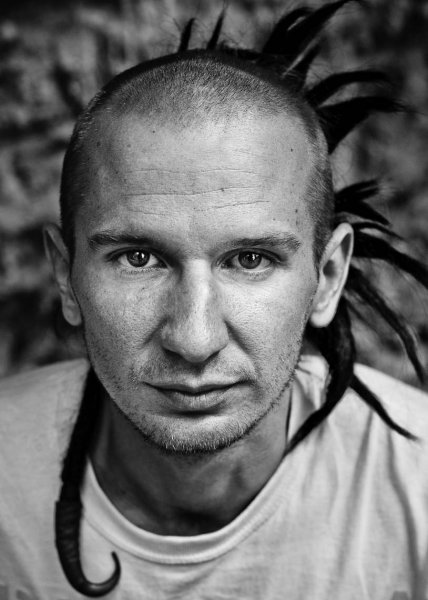

Cory Richards and Jason Kehl, at first flush, present a case study in divergent disciplines within the same sport. Richards finds his inspiration at altitude, chasing his alpinist’s vision with groundbreaking results. In 2011 he became the first American to climb an 8,000 meter peak in winter, a daring ascent that barely saw him down alive. That winter ascent of Gasherbrum II landed him National Geographic’s Adventurer of the Year for 2012. Kehl, a bit closer to terra firma, has lived on the cutting edge of highball bouldering for nearly two decades, capped by first ascents like Evilution (V12), The Seventh Circle and Count to Six and Die (both V13 and unrepeated), while “bouldering” routes like Straight out of Squampton (5.13+) and The Fly (5.14d). He has more sketchy FAs under his belt than wacked-out hairstyles, which is seriously saying something.

One is foremost an alpinist, the other mainly a boulderer. It’s like comparing Ronnie James Dio to Vivaldi, right? Well, not exactly.

Both alpinists and highball boulderers face down the same albatross, an unrelenting struggle between risk and reward. They tinker with morphing and shifting waves of fear, sometimes illusory but all too often very real and hitched to life-altering consequences. One may be classical and the other heavy metal, but they’re both tinkering with the same notes and building from the same root scales.

Besides climbing at the top of their respective games, both Richards and Kehl bring prolific artistic sensibilities to the table. Richards is a professional photographer and filmmaker, landing photos in publications like National Geographic magazine, Outside and the New York Times. His film, Cold, won the Banff Mountain Film Festival’s prestigious grand prize award in 2012. Kehl is one of the foremost climbing hold shapers in the industry and owns his own company, Cryptochild. He’s made dozens of films, both short and feature length, notably The Zanskar Odyssey and The Seventh Circle.

This is my favorite interview I’ve ever been involved with, for a number of reasons, the foremost being that it isn’t every day you get two world-class athletes in a room together, from opposite ends of the climbing spectrum, breaking down the battle of fear and risk/reward they so often tackle. The fellas also talk about filmmaking, the sustainability of climbing, climbing as a lifestyle or a sport, sponsorship, the inspiration to get on a particular line and why we do all this crazy shit in the first place.

[This interview, although previously unpublished, is from late 2012, recorded live in the studio on the ClimbTalk radio show.]

Mike Brooks: You’re listening to ClimbTalk on Radio 1190. My name is Mike Brooks. Dave McAllister is the co-host. We have Jason Kehl and Cory Richards in the studio. John Sherman’s going to be calling us from Arizona. Looking forward to that. He has a new book out, called Better Bouldering 2. Jason and Cory, thank you for joining us.

[John, we found out later, had been trying to call but received a busy signal the entire time. He never got through.]

Jason Kehl: Thanks for having us.

MB: Cory, the Adventure Film Festival is going to be coming to town in a few days and you have a new film out, right?

Cory Richards: Yeah. Cold is going to be playing. It’s a film that we did last year in Pakistan during the first winter ascent of Gasherbrum II. I’m excited to see it play at the festival.

MB: We were talking earlier; why in the winter?

CR: [laughing] That’s a good question. Everybody wants to know why…why do we do it in the winter? It’s like adding suffering to suffering.

Back in the ‘80s, the Polish climbers were kind of fed up with the mass amounts of people that were overtaking a lot of the Himalayan peaks. They decided to sort of wipe the slate clean. One of the ways they thought they could do that is by doing it in the winter. So, it sort of erases all of what’s become known as the “Everest infrastructure.” It takes away all the ropes and the people and you’re doing [it] sort of how it was meant to be done.

MB: So, you didn’t have a support crew?

CR: We had a couple people in base camp, helping us cook. That’s it.

MB: That’s pretty hardcore. Tell us about the movie.

CR: When I came back and I was looking at all the footage, it became very obvious that the film, if there was going to be one created, really needed to be told from the inside of my brain. A lot of times these things get overblown and it becomes a sort of heroic adventure and bla bla bla and the wind’s blowing and all this. Realistically, I think the experience is a lot different than that. So, I think the film is more about doubt and figuring out what’s going on in my own head during those times. I think it humanizes the whole experience to a different level and it makes it a lot more accessible.

DM: When you’re shooting a movie like that do you go into the climb (you just had a small hand-held camera, I know) with a vision already amalgamated in your head or does it organically come about as the trip progresses? Or, does it happen after the trip – you just take your footage, and, “Do I have a narrative that I can show people and be interesting?”

CR: I think all adventure film comes together in a different way and it can be any one of those three. For me, on this trip, my job was to be capturing the trip. The film, as it came together, was basically the last option there. I came back and we looked at everything. Probably, out of nearly a terabyte of footage, we used maybe one percent to create the whole film. It takes a tremendous amount of footage and material to ultimately come together and start looking at things and saying, “How can we tell this story effectively and make it accessible to people?” So, it was much more, in this case, coming back and saying, “This is what we have and this is where the story works.”

DM: Telling a compelling story isn’t always easy…

CR: No. Especially about mountaineering! Let’s be honest, it’s not the most exciting thing sometimes. Most days when you’re going alpine climbing you’re sitting in your tent worrying about climbing. That’s not really exciting. You’re just sitting there scared going, “How’s this going to play out? This is terrible! I’m just scared all the time.” That footage is not really compelling.

Looking back on how much we actually came back with, it was pretty staggering to see the amount of footage we had created. And how much of it was absolutely useless. There’s just so much that’s not that interesting.

DM: Right, it just doesn’t add to the story at all. It’s just you guys cooking tea…and weather reports.

CR: Yeah, one night we were making pizzas in the tent and I got at least 40 minutes of “making pizza” footage. I’m not sure how that would ever add to an alpine film, but I’ve got the footage in case anybody wants to make a film about making a pizza…I got it. Alpine pizza making.

DM: You guys came back with a compelling story, though, regardless if you shot footage or not. So, we know that you ascended Gasherbrum II. You’re the first American to [summit an 8000 meter peak in the winter]. But that’s only half the battle. Of course, getting off the mountain is oftentimes more dangerous than ascending. Tell [us] what happened on your way down.

CR: It’s a really good point to make. So often people view climbing mountains…it’s more digestible to think of climbing to the top and when you climb to the top you’ve somehow succeeded. There’s a good quote that says, “Going up is optional but coming down is mandatory.” That was Alex Lowe. He didn’t come down one time. That concept is very prevalent. As soon as you get to the top of a peak like that you realize that pretty much I’ve spent everything I have getting here…and I’m only half way. Getting down becomes scary because you’re exhausted and you start making some bad decisions.

On our sixth day out we were trying to make it back to base camp from camp 1. We were exhausted and we were tired and it had been snowing now for two days straight and the winds were super high. Avalanche conditions were getting worse and worse. We basically were traversing under a massive slope on Gasherbrum V. The snow was about waist-deep, so you can’t really move that quickly. Moving in that sort of terrain…it’s basically a terrain trap. For anybody who doesn’t know what that means, it means you’re in an area where you’re basically trapped to whatever happens around you. It usually refers to avalanches.

We were trying to traverse this plateau that’s also horrifically crevassed and an avalanche was triggered by a crevasse falling about 3000 feet above us. It came down and it came out of the clouds and it came fast and it hit us all, pretty much full bore, as frontal as you can be hit. We got carried about 500 feet…

You know, I try to paint the picture of being in an avalanche and what that’s like, and it’s basically like being in a Maytag, except it just keeps getting darker and darker and darker. You’re trying to swim against it, you’re trying to do everything you’ve ever been taught to do in an avalanche, and it just doesn’t work. And there’s a lot of time to think. It just gets darker and darker and darker and pretty soon you realize that you’re being pulled to the bottom and as soon as it stops you’re going to be screwed. That’s just it. Especially, the size of the avalanche that hit us was just something you don’t walk away from. There’s sort of an immediate acknowledgement of the fact that you’re dying.

For whatever reason, when we stopped – we were all tied together, which usually works against you in this case. It didn’t. I got pulled upright and ended up lying on my side with my face out of the snow. My face and a piece of my arm. In that moment, my first thought was…I was really angry because I thought, “My partners are dead, obviously. There’s no way that all three of us survived this. And now I have to figure out, how do I get down by myself?” Because there’s nobody there to help you and really nobody knows that you’re there. You’ve got your base camp staff, but that’s it.

Then, I heard the voice of one of the other climbers, Simone [Moro], and he asked if everybody was okay. I thought, “Everybody? That’s odd.” And then I heard Dennis’s [Urubko] voice and he said he was okay. I couldn’t see because I was completely trapped. The next thing I knew Simone was digging me out. As soon as I could sort of move he left and went over to Dennis and started digging him out. It took us about fifteen minutes to get out of it, to the point where we could all move. I turned the camera back on at that point and that’s sort of the second climax of the film. Certainly, for me the emotional…

MB: And that’s going to be at the Adventure Film Festival, November 3-5?

CR: Correct. Cold is playing on the night of the 5th and I’ll be there to talk about it, as well. Again, I’ve had one film in Adventure Film before and this is my second, but I’m really, really excited to see this one there.

MB: That sounds good. In the studio we have Jason Kehl, as well. Jason, you have a couple flicks in the Adventure Film Festival, as well, right?

JK: Yes, I have two. The Zanskar Odyssey, which just got released on DVD and digital download. That and The Seventh Circle, which is a long-time project I had in Hueco Tanks.

MB: So, you sent your project?

JK: Yes, finally. Three years working on the same thing.

MB: You guide down in Hueco, as well, right?

JK: Yes.

DM: This is your second season guiding. You’re guiding, what, four days a week? Five, three days?

JK: Whatever you want. You can go out every day if you want.

DM: Do you have any stories about cantankerous boulderers who want to break apart from the crowd? Because I know when you’re guided down there the group goes to one boulder, and then they go to another…

JK: I’ve never had it on my tour, personally. But, I’ve been on some tours. I remember, we were down there and we were filming Best of the West, with Chris Sharma and Nate Gold and a couple of other guys. An old friend of mine who has been a guide forever, J-Bone; we were just kind of all over the place and he kind of snapped at us at one point. It was like, he’s going to turn this tour around right now.

DM: Like a dad driving a car on vacation…

JK: Yeah. You really have to obey the rules and respect the place. I think people forget that, especially when they’re used to going to other areas that aren’t as crazy as Hueco Tanks.

DM: I have a question for you, Cory. I want to step back to what we were talking about with the avalanche, because that blows avalanche statistics out of the water, what happened to you guys. That’s – I hesitate to use the word – miraculous.

CR: Yeah, I’ve had a couple people come up to me and they’re like, “Where’s your faith?” In fact, I was in an event the other night and somebody asked, “Do you have any specific religious affiliation that you’ve picked up after this experience?” I was like, “Uh…no. Anything that advises staying away from avalanches would pretty much be my religious belief now.”

It is miraculous. All of us…just don’t know how… It just seems silly. I don’t have an answer for it. It just defies logic.

DM: You stole the words out of my mouth. It defies description! What can you say that would do that moment justice?

CR: The moment of knowing you’re alive or the moment of knowing you’re going to die?

DM: And all the attendant moments that happen after that, as well.

CR: I think that second where you’re like, “Wow, I’m on top”…it’s so brief because you’re instantly drawn back into the environment and the fear that you’re experiencing in that sort of situation. Take any moment where you’ve felt a great amount of relief and multiply it…infinitely. I guess that’s how it feels. It’s hard to really capture in words.

DM: I have a question about the fear, the fear that you experience, generally, alpine climbing, in the hostile environment at 8000 meters. That’s a visceral fear. It’s not some esoteric fear that’s prancing around in the distance – it’s in your face. Is that something that you can be prepared for when you enter that realm for the first time or is that something you have to face – nobody can train you, nobody can teach you? I guess my question is: What is it like to come face to face with life-or-death fear, visceral fear, for the first time?

CR: I think we experience different elements of fear throughout our entire lives, so you’re basically training for it forever. It’s really not that different, I think, to the fear that Jason feels when he’s doing a super-highball, dangerous boulder problem. It’s very much the same. I think the difference is that when you’re alpine climbing it’s not so acute. It’s not that fear of “I don’t want to fall off the top.” It’s drawn out over a much longer period.

Facing it for the first time, or facing it for the most recent time, always seems to be the same. It doesn’t really matter how much experience you have. I think it’s probably the same for Jason. You can have a ton of experience, but fear is fear, and it smacks you in the face.

JK: I try to remind myself that it’s just a feeling. A lot of times I’ll look at things that I want to do and I’ll feel this fear, but it’s just this feeling that you create. When you are in the moment, if you are feeling fear, you’re creating that fear yourself. For me, anyway, because I’m aware of it and it comes and it goes.

DM: But, you’ve suffered the consequences of your fear. I’ve had consequences…like, bodily; broken bones. Doesn’t that change the validity of the fear a little bit?

JK: It tries to, but you can’t let it.

DM: I agree with you 100 percent…but it’s hard.

JK: The more you realize what it is, the more you’re going to fear it.

DM: I know…it just circles back on itself. You’re right; you have to overcome it. But, I feel like after the fear is gone and the consequences are there – you’re not fearful anymore, you’re just kind of screaming, waiting to go to the hospital – then that’s a whole different paradigm.

JK: If you’re not pushing it to that point, then what are you doing?

DM: I couldn’t agree more…

CR: You can’t recall on that experience and just worry that the same thing’s going to happen. At the same time, I think there’s a big difference between intuition and just straight-up rational fear. Most of the things we feel, that’s just rational fear. That, I think, is what Jason is addressing when he says “it’s just a feeling”. Intuition is something totally different.

Finding the line between the two is often very, very, very difficult. I’m certainly not saying that I’ve managed to find that, but there are times when you just decide to turn around because it doesn’t feel right. That’s different than saying, “No, this is just rational fear and I’m going to work through it.”

DM: Yeah… That’s indescribable, as well, almost. Both healthy. Intuition is a necessity for all climbers in all disciplines and rational fear keeps us safe…

I have another question. I don’t want to be an alpine climber. I admire the hell out of it but I never want to be an alpine climber. But, I’m fascinated…

CR: I actually don’t want to be an alpine climber either [laughter].

MB: What do you mean by that, Cory?

CR: First of all, what’s your question and then I think I’ll answer that one with it.

DM: Probably. Do alpine climbers have an innate proclivity to suffering or is it that you’re drawn to alpine climbing, like “I really want to do that,” you get there and you’re just pummeled by the suffering and you learn how to deal with it? Or, is it some strange, awful gift you’re born with?

CR: Or is it a gift of masochism? I think, basically, you’re drawn. For me, I’m very much drawn to that environment. I’m drawn to very, very big places and I’m drawn to the feeling I get from being there, which is sort of a feeling of insignificance and realizing that there really is no control. I can do everything perfectly and still get caught out. Experiencing that, or having that love for those environments, you just kind of take what comes with it. A lot of times that is suffering.

I usually joke, “It’s Type 10 fun, it’s the type of fun that doesn’t have to be fun to be fun.” When you’re in the moment and you’re doing it it’s much more like work than it is fun. But then when you wake up in the morning and you look out that tent and you’re looking at a 7000 meter peak that’s just getting first light, that’s why you’re there. Realistically, the whole experience is fun, but it’s a different manifestation of that word.

DM: Yeah…it’s like “retrospective fun.” During the day you’re like, “This is awful, this is crushing my soul!” And then the next day, you’re like, “Hey, in retrospect, that was fun!”

CR: Well, there’s something to be said for when you have a tough day and come home… I mean, just going out for a run and you’re running through sleet and you come home and you’re cold and you’re like, “Yeah, but I totally did it. And that was rad.” I think that exists, again, in any discipline of climbing. It’s just, expedition climbing or alpine climbing basically takes that bell curve and stretches it at both ends and makes it…longer.

DM: I’m going to bandy the same question that I just asked Cory [to Jason]. Some people are drawn to alpine climbing. Madeleine Sorkin, who was on last show, is drawn to gnarly, dangerous trad climbing. And you’re drawn to bouldering. What draws you to bouldering?

JK: The simplicity, for sure – shoes and a chalk bag. And I like the fact that I’m always aware that I’m falling to the ground. I hate rope climbing because I fall and then I get pulled into the wall. I like being aware of my surroundings and what’s going on and how I’m going to react. I really like the discovery aspect of it, doing first ascents. Discovery and creation, you know; you see something and you wonder if it’s possible and then you do it and then it becomes this thing.

I would always say that bouldering is similar to trad climbing in the sense that you’re taking the purest line. There’s one way up the boulder, same as a crack. You top out. In sport climbing you do not top out. So, I always feel this connection. I enjoy trad climbing for that aspect. You’re taking the purest line and you’re not using any gear like bolts. It’s somewhat free, same as bouldering. You’re summiting something.

DM: Unless you’re at Morrison…

JK: Yeah…don’t do that. [laughter] But, I hear there’s stuff on the other side – across the road – that you can top out.

DM: I was just there on Sunday. There’s some really good stuff over there, in all seriousness.

MB: So, you like to boulder at Morrison, Dave?

DM: No, I’m not… Yeah, I’m not ashamed! Don’t judge me! Morrison’s fine. In the middle of the winter. When it’s raining. Where else you gonna go? Into a gymnasium with rock grips and toe holds? I don’t think so. [laughter]

[There’s some speculation as to why John Sherman hasn’t called in yet.]

DM: I have a question that I wanted to ask Sherman that I want to ask you [Jason].

JK: Oh, no. Should I use Sherman’s voice?

DM: So, we had Jamie Emerson on a couple shows ago, who’s a pretty insightful, cerebral guy when it comes to climbing. He was talking about the progression – I hate that word, it’s like a thumbtack in my brain – of bouldering, and he cited you, your trip to the Himalayas, The Zanskar Odyssey. You as well, Abbey [Smith, who is also sitting in the studio]. And his trip to Alaska. And I guess there’s a crew up in Idaho that takes a boat for a mile and then hikes six miles into the mountains. He proposed that the future of bouldering is these sort of extreme adventures, just traveling farther and farther. You think so?

JK: Definitely. There’s so many people into climbing these days that it seems like you go to a popular area and it’s going to be crazy crowded. So, what do you do? You walk another hour to the next area and it’s not that crowded. And maybe the next year people find out about it and you go out there and it’s crazy again. We’re always looking for something untouched. That’s what I’m looking for.

DM: You think all those people are sustainable?

JK: No, no, no. I actually wanted to bring up this question to Mr. Sherman, because we both participate in the same activity. We love the outdoors and we want to get away from it all, but at the same time we’re promoting it, which crushes our dream.

DM: That’s a sad thing to say.

JK: Yeah, we want this one thing, but to have this we have to promote it and turn it into something else. Therefore, we have to run even farther. With books, Better Bouldering, or with films, we’re expanding the sport and I don’t think the earth can really handle it.

DM: It can’t, right? It’s apparent and obvious to anybody that holds will get polished and the environment will be damaged.

JK: [to Cory] It’s the same thing that you were saying in your show last night about Everest.

CR: Well…just the fact that the whole point – it’s sort of consistent through all climbing – the whole point of going and doing something in the winter is getting away from everybody. It’s the same thing that we’re talking about. You run as far as you can from the crowds. What happens is you go to these incredible places and you make a really great film, right? And then people are really inspired to go there. So, all of a sudden you’ve taken this wonderful, utopic ideal of finding the most untouched place, and you’ve basically broadcast it to the world.

But, that’s also very necessary to perpetuate the sport on a commercial level, which is beneficial to all of us in terms of better shoes, better climbing gear. All that money goes back to R&D and then goes back to sales, which helps people go climbing. So, it’s a double-edged sword. Is it a good thing or is it a bad thing? I don’t know. It’s just sort of the way it is.

DM: Super contentious issue…

JK: I think it’s bad. I think it’s real bad.

DM: The promotion of climbing?

JK: I think it’s all real bad.

DM: You’re in such the wrong business, bro.

JK: I’m in it and I can’t turn back.

DM: There’s a lot of people, in this city especially, who would bang their heads against a door hearing people say that the money generated by these promotional tools somehow helps the sport. They would say this isn’t a sport, this is a lifestyle. I mean, we’re in the business, too. We’re a climbing talk show. So, we’re all in the same boat. But, they’d go crazy saying you’re ruining a lifestyle and creating a sport.

CR: I don’t know what I’d say to that aside from, “How did you learn about climbing?” Inevitably, their answer’s going to be, “Well, I saw it in a magazine.” And then, “What magazine was it,” whether it’s Outside, Climbing, Rock and Ice? And maybe some of the old guard is like, “We just went climbing.” Yeah, that’s a pretty natural human instinct. We go climbing.

Most people that have that gripe with too many people climbing and it being a sport are not in touch with where they came from. I’m not afraid to say that. Yeah, it is a sport. And, you can make it as much of a lifestyle as you want it to be, but it’s still a sport. The lifestyle and the sport are two very different things. Just because you’re a climber doesn’t mean you have to live in the back of a car. Likewise, just because you live in the back of a car doesn’t mean you’re a climber.

DM: Mike, I guess you can move back into your house.

MB: There ya go! Cory, you have a flick coming up in the Adventure Film Fest, and I was going to ask why it was called Cold, but I guess I already know that.

CR: Yeah, it was a really creative naming process:

“What should we call it?”

“What did you feel?”

“Cold.”

“Alright, sweet. We got our title.” [laughter]

That was pretty much it. That was the conversation.

MB: How did you guys afford that and what kind of equipment did you need or take?

CR: That goes back to the last question that we were sort of debating. I’m a climber for The North Face and these huge expeditions – the only way they happen is if you’ve made a ton of money in the stock market or you have a very, very big sponsor. It costs a lot of money. You’ve got plane tickets, you’ve got food, you’ve got all the equipment, you’ve got all that production cost. It costs a tremendous amount of money. At the same time, those companies promote and get behind these sorts of trips in order that they can get feedback on their gear and they can actually make gear that works.

Again, it’s almost exactly the same thing we were talking about, in terms [that] it’s a necessary evil. We wouldn’t be able to do it…I wouldn’t be able to do what I do without a sponsor like The North Face.

MB: Did you guys use oxygen?

CR: We did not. We used aspirin, though, because that thins your blood. It’s awesome! Maybe we copped out…

DM: I keep breaking away from the films that we’re supposed to be promoting, but I’m fascinated by you two guys sitting here. We have a guy from the alpine world – and I know you’re an all-around climber, as well – and we have a guy from the bouldering world. The two extremes of climbing.

But, you guys both face something similar, when you’re talking about risk versus reward. Jason, I know you’ve done super-dangerous boulder problems. And, of course, every time you step into the alpine realm – I mean, Gasherbrum II in winter, give me a break – it’s dangerous. So, how do you entertain the ratio between risk and reward? How do you balance those scales before you step up to the plate on a dangerous route or boulder problem?

JK: I think there’s always a sliding rule there. You’re looking for something that’s dangerous, but at times maybe you’re not willing to push it. You can’t just go first day out and [say], “I’m going to go for the biggest, scariest thing.” The process is more interesting to me. Like, you’re saying these things I’ve done are scary, but I think they just look scary to you.

DM: I mean, I’ve stood under Evilution, and it’s scary.

JK: Yeah, it’s scary to me, too. But, you have to break that down. Like I was saying earlier, it’s a feeling. It looks really scary, this thing I want to try in Hueco. As soon as I walk up to it I’m freaked out, looking at it and looking at the landing. I’m like, “Oh, wow. That’s messed up. What am I doing?” And then, I keep going back and I keep forgetting that feeling. I just kind of break it down, like, “This is possible. This isn’t dangerous. It looks dangerous, at first glance.” The more you break it down, the less dangerous it is.

DM: That sounds like semantics, man. [laughter] At first it is dangerous and then only looks dangerous? I mean…

JK: It’s all in your head. At the end of the day it’s all the same boulder problem. You could fall off the top of something and totally land it and not expect it. If you’re standing on the ground and look up there and [you’re] like, “I don’t want to fall up there, if I fall up there I’m going to split my head open,” that’s just a feeling. When you do fall off, accidentally, and you land in the bush, you’re like, “Wow, I’m fine.”

DM: So, you definitely think about the risks.

JK: Oh, yeah. You have to.

DM: Have you ever walked away from something…

JK: Oh, yeah. All the time. Easy stuff. [If] I’m just not into it or if people are trying something and I’m just not feeling it, even if it’s well within my ability, I’m just like, “No…I don’t want to do this. This looks sketchy to me.” It’s whatever turns you on. You have to be passionate about it. You have to want to do it.

DM: The personal reward has to be high enough.

JK: Yeah. I think a lot of people get injured on things that are under their ability because they’re not as focused. They forget about it and they’re just like, “I’ll just do this. I can do this.”

DM: Or, there’s peer pressure. You’re with a group, everybody’s doing the highball, you’re not into it. Been there. What about you, Cory?

CR: I think the reward has to be worth the risk. For me, I want to do stuff that’s inspiring. You look at them and you’re like, “I’m really inspired by that face on that mountain.” And then you start to look at it objectively and go, “How dangerous is that line that I’m looking at? Is the line worth the inherent risks that surround it?” For me, am I inspired to do it? If I am, how inspired am I to do it? And if I’m really inspired, is it worth everything that might come with that? I think every time it’s different. Every single time.

It’s so funny. We talk about bouldering and alpine climbing being at the two opposite ends of the spectrum, but at the same time, the emotions that you’re feeling [are] exactly the same. They’re just more acute or less compressed. Climbing is the same, pretty much across the board. It’s just the motions that are different. We all experience the visceral feelings the same way.

DM: The temperature’s a little bit different.

CR: Yeah…bouldering in -80! Jason takes it to a new level… [laughter]

JK: Summer ascents would be more impressive. A summer ascent of Nagual, in Hueco. It’s, like, not going to happen.

DM: Alright, we said the “I” word, inspiration. This is perfect. I love having both you guys here. What inspires you or draws you to get on a particular climb?

JK: Just the purest line, really. What I’m looking for is something I’ve never seen. It’s just so crazy; there’s an interesting feature on it. It just stands out, you know? Also, it looks impossible. That’s the illusion that I like because that’s what I’m trying to break down. I’m trying to break down the illusion. The cool thing is when someone first walks up to it after the fact and they’re like, “Some dude climbed that. That’s super-messed up.”

Definitely, the ascetics are super-important to me. Not about the grade, at all. People are like, “How hard is it?” I’m like, “I don’t know, dude. You should try it and see how hard it is for you.” It’s all challenging. A V0 boulder problem is challenging. It makes you think. You have to engage. Just, being more focused on the beauty of the line and also the illusion of danger…I’m trying to pull that off and make it clean and nice and beautiful.

MB: What do you think about that, Dave? That’s the third time he’s mentioned or implied the illusion of danger. Is that oxymoronic?

JK: No.

DM: We’re getting into some existential word games here. It’s a little bit oxymoronic, but I understand what you’re saying. It’s an illusion if you…

JK: …can break it down and understand it…

DM: …and climb it safely and in control, then danger becomes an illusion. Because, as much as you can be in control in the natural world, we have to know we’re not in control…but as much as you can be, then that danger becomes illusory.

JK: Say, the beginning section is super easy but it’s over this crazy crevasse boulder jumble – you don’t fall there. The next part is the crux. It happens to be in this nook of rock where you can put a couple of pads. If you fall on the crux, which is the most likely [place] you’re going to fall, you’re going to be safe. If you fall after that maybe you won’t be too safe, but at that point it’s more of getting it into your body and understanding it so that you slowly start to break down that fear. And then, you just do it. There is no fear at that point.

DM: We were talking, before the show started, about Worst Case Scenario, a boulder problem in Joe’s Valley that Jason put up that I was on recently. It’s exactly what you’re talking about.

It’s [just off and above] the road, kind of on a cliff face. I imagine you called it Worst Case Scenario because if you take the worst fall you could possibly take on that, you’re spitting 30 feet into the road.

JK: Yeah, totally.

DM: It looks so dangerous, but then when you get on it you realize, “Oh, that’s the easy part.”

JK: Totally. Does the name help add to that danger?

DM: Yeah! It scared the…um…feces out of me.

JK: And that’s just a feeling, too. You read a name and you have a certain feeling, already. It’s not called Purple Flowers. It’s Worst Case Scenario. I think that’s important. And I think that’s just part of the illusion.

CR: I can’t really add to anything that Jason said, as far as what inspires you. It’s the same thing. That’s why I think it is very, very similar throughout all genres of climbing. Alpine climbing, you’re just psyched when you see a big face. You want to pick the most ascetic line and you want to do it in the best style possible. And it looks impossible, because it’s huge, but you go for it anyway.

The only difference is that when you’re alpine climbing your objective hazards are much, much greater. When you’re bouldering, probably the thing that’s going to spit you off, that you don’t have a ton of control over, is, say, a hold breaks, and you’ve got a lot of tension on it and you go spinning off and land in the road. When you’re alpine climbing, you could be approaching something and there’s a serac or crevasses…there’s a lot more to the environment that’s going on. I think that’s really the only thing that differs there. It’s really about choosing your ascetic line. It’s about choosing something that looks impossible or improbable and putting all those pieces together and then looking up at it and, “Somebody’s been there.” Or, “I’m going to try to be there and do that.” You just have to weigh out those hazards in the alpine realm a little bit more… I don’t want to say “more carefully”, because that’s not right. You just have to take all of them into account.

MB: How do you rationalize dealing with so much objective danger?

CR: I try not to…because I can’t. There’s no rationalization for putting yourself in harm’s way, aside from the fact that you’re just truly passionate about what you’re doing. Throughout climbing, I don’t think anybody needs more of a rationalization than that. If you love what you’re doing and if you’re psyched to be doing it, then that’s it. That’s all.

DM: Cory, I’m going to read you a quote that I read, that you said: “The truth is I’ve never excelled at anything athletic. In fact, all of my athletic endeavors have been defined far more by mediocrity than excellence.” Expound on that.

CR: [laughter] Well, I started doing this as a photographer and I started climbing being in this bigger climbing world as a photographer and as a writer, as well. I was mediocre at all of that, too. I still honestly believe, as an athlete, that is not in any way what defines me. What’s ended up being my greatest asset, what is probably very similar between the two of us [speaking to Jason], is the mental fortitude that you have to grasp in order to get over these obstacles, whether it be super-highball bouldering or alpine climbing. It’s more about what’s going on upstairs, and like Jason’s talked about this evening, understanding that this is just a feeling. It’s more about that mental capacity than it is about muscles. Certainly, your muscles have something to do with it. I’m not going to lie and say that anybody can do this. But, more people than we think actually can go out and do this. It’s just finding their outlet.

JK: Yeah. You could be the strongest guy – the strongest hands – and if you don’t have the mental aspect you’re not going to do anything. You can’t get up the wall.

CR: Conversely, you could have not so strong hands and have an incredibly strong mind and get up it. That quote… A lot of people like to ask me that question, but I stand by that. My athletic endeavors have been defined by mediocrity, it just so happens that this one caught some attention. But again, it’s about what’s going on upstairs, not necessarily what’s happening in your body.

MB: Cory, what’s next?

CR: Next… I got invited to go back to Pakistan this winter [to] try to do the first winter ascent of Nanga Parbat, which is another 8000 meter peak, and I turned it down.

DM: Why is that?

CR: I turned it down because it doesn’t inspire me. It’s not something I’m excited to go do. I love the mountain, but I’m not drawn to go do it in winter. There’s other 8000 meter peaks that I want to do I winter, but I’m not going to do that one. I just don’t feel good about it.

The next thing that’s on the list right now, I’m headed back to Nepal this spring with Jimmy Chin and Conrad Anker to try and repeat the first American ascent of Everest, which was done in ’63. That’s the West Ridge to the North Face. That’s the next big project.

DM: Serious photography power up there. Holy cow…you and Jimmy Chin.

CR: Yeah, you can kind of point your camera in any direction and you’re just like, “Sweet. I got it.”

A parting screen shot from Cold…you get the idea. If you haven’t already, see this movie. Like, right now.

DM: I have a question about Pakistan. Say somebody’s listening who’s working at a gas station right now and enthralled by this and they hear, Pakistan. “Americans are going to Pakistan to climb!?” I think there is probably an obvious response that people would say, “In this political climate how could you ever climb in Pakistan?” You want to dispel that myth?

CR: Yeah! I’ve traveled a lot in Asia and immersed in several different cultures over there and I have to say that the Muslim culture, especially the one that I encountered in Pakistan, was the kindest, most accommodating, most hospitable culture I’ve ever found myself to be a part of. These people are incredible. They’ve got a one-room house with five kids. You come in and they cook you dinner and they make you sleep on their bed and they sleep on the floor. It’s that kind of culture, where it’s like, “You have way too much and we don’t have nearly enough, but I’m willing to give you everything I have just to make sure you’re comfortable.” And what we hear about Pakistan on the news…it’s just…it’s false, most of it. It’s blown out of proportion.

DM: What did Bob Dylan say? He said something like, “I don’t read Time Magazine – they have too much to lose by telling the truth.”

CR: Exactly. We have so much more to gain by cooperating and being friendly with these countries that we’re so fearful of right now. But, that doesn’t work in our current political climate. I’m not going to say that I’m a political activist, but as much as going to these places and bringing back that culture is activism, I’ll continue to engage in that. I think first-hand experience tells a lot more than what we see on C-SPAN.

[…] Check out one of my favorite interviews with Jason here. […]